Nayla Maaruf – Conservation treatments do not always work out the way we want them to.

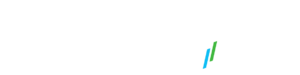

As conservators we research, consult with colleagues and do testing before a treatment. But even with all the time taken to ensure a treatment is right for the historic objects we work on, what we do can sometimes turn out not as we anticipated. In these instances, a treatment needs to be revisited and redone with a different approach, and sometimes with different materials. This was the case for a 16th-century book with wooden boards in the National Art Library (NAL) collection at the V&A. The front board was in two pieces, possibly due to the shrinkage of the alum tawed skin on the spine, which had caused the book board to lift upwards and to dramatically split along the edge of the spine covering, probably through handling and or pressure on the board.

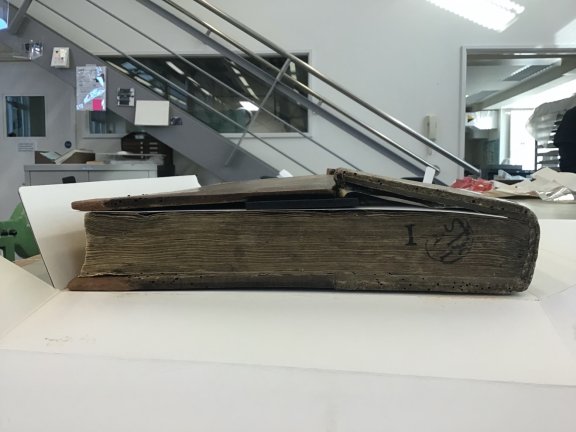

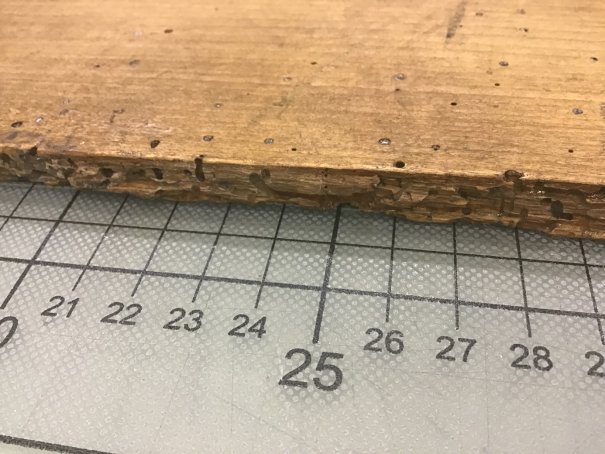

A recent treatment using a resin adhesive, Paraloid B72, to glue the two pieces together, failed soon after it was applied (above), leaving a layer of resin on the broken edges (below). There was also significant pest damage to the wood. The resulting loss of wood from the insect activity complicated the task of re-attaching the two pieces, as there were fewer contact points for an adhesive to attach to. We wanted to display the book, so it was imperative for the board to be in one piece – as well as to ensure the long-term preservation of the binding.

We needed to address two elements. First, the lifting of the board caused by the shrunken leather. Second, the attachment of the two board pieces. The previous treatment adhered the board together, but did not support the space between the lifting board and the text block. We decided to insert a bespoke wedge at the front of the book that would permanently stay inside while the book was stored, supporting the front board. We carefully measured the angle required and made a supportive wedge from archival corrugated board.

We consulted with furniture and frame conservators on a new treatment plan for the attachment of the two broken pieces. The problems were the lack of contact points between the two edges, and the disparity in size between the two pieces, with one larger, heavier piece causing a stronger downward pull. For these specific issues, we considered using dowels; holes would be drilled into both edges for the dowels to form a more stable connection than adhesive alone.

There were several complications with this intervention. It is quite challenging to drill perfectly aligned holes, but more importantly, it is very difficult to justify creating new holes in an object. Ethically, there would need to be a very strong case to change and remove part of the original, even though from a general public view they would be rather small holes. Nevertheless, after careful consideration, we concluded that this book’s specific ailments required this somewhat drastic approach.

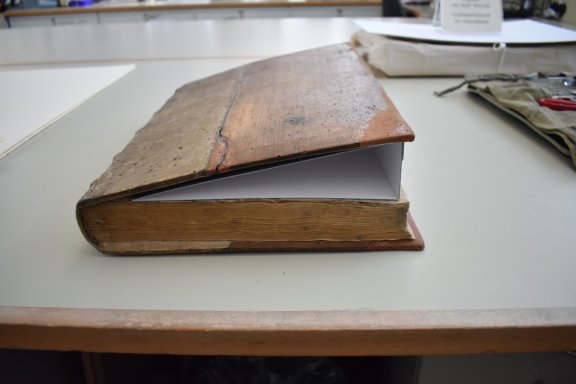

For the dowels we used glass-fibre rods of 0.3 cm diameter cut to a length of 3 cm. Glass-fibre was chosen because of its stability and strength; although wooden or metal dowels could have been used, each have their drawbacks: wood shrinks and expands with changes in relative humidity and temperature, which can lead to loosening or cracking; metal pegs can rust and, over time, cause significant issues. Glass-fibre won out because it is a strong inert material that will not expand or contract.

As the dowels alone would not provide enough support, we also chose an adhesive to help keep the dowels and boards in place. In keeping with historical materials, we used an established adhesive historically used in woodworking and commonly in conservation: hide glue. It is water-soluble and has fairly good aging properties.

Before any dowels could be put in, or new adhesive could be applied, the resin adhesive needed to be reduced. Paraloid B-72 is dissolvable in ethanol, acetone, toluene or xylene. To remove the B-72, it needed to be soaked in one of the solvents and mechanically scraped away. To accomplish this, we soaked pieces of Nanorestore gel in acetone and placed them on the edges of the board, then, the softened, malleable resin was removed using a porcupine quill. Conservators use porcupine quills because they are hard enough to pick up sticky substances, but soft enough not to cause scratches or damage to the surface of a wooden object. Unfortunately, it was not possible to remove all the resin.

After removing as much resin as possible, we drilled the holes for the dowels using a hand drill. We placed four dowels, two inset 4 cm from head and tail edges, and two evenly spaced in the centre. After the two pieces were joined, the resulting gap was filled with a putty of hide-glue and paper using a syringe. Adding paper fibres to the hide glue reduces shrinkage when it dries, which results in a bulkier, more stable filler for consolidation along the breakage. A mixture of 3:5 fibres to hide glue was liquid enough to in-fill the missing areas, while having enough fibres to reduce shrinkage as desired. The final result was a stable bond with additional support provided by the dowels when on display.

Vietnam Plywood

Vietnam Film Faced Plywood