By Paul Sellers – it may not seem like me: you might well be surprised, but my history with plywood dates back to my earliest recollection of woodworking with my dad in 1960. I know! Time passes when you’re having fun! That was 59 years ago! It was springtime when I sat on the kerb outside my house. Trucks went past every few minutes loaded with household rubbish piled high. Just open truckloads. I happened to look up and a different truck went by and I saw a truckload of what looked like pure white wood. Stockport’s town dump was a block away from my house within a triangle of railway tracks–‘the bottom field‘. I raced pellmell down the street to the dump to see what it was just as the truck swung around in a big arc and dumped its huge load. The bulldozer, a massive thing, took the plywood before its blade to the cliff edge of the mountain of refuse and shoved the pile in a single push. Running home and out of breath with the run and the excitement of it I knew somehow that this would be a prize find. Waiting for my dad to come in from work I could scarcely contain myself knowing that he too would feel the same as I did.

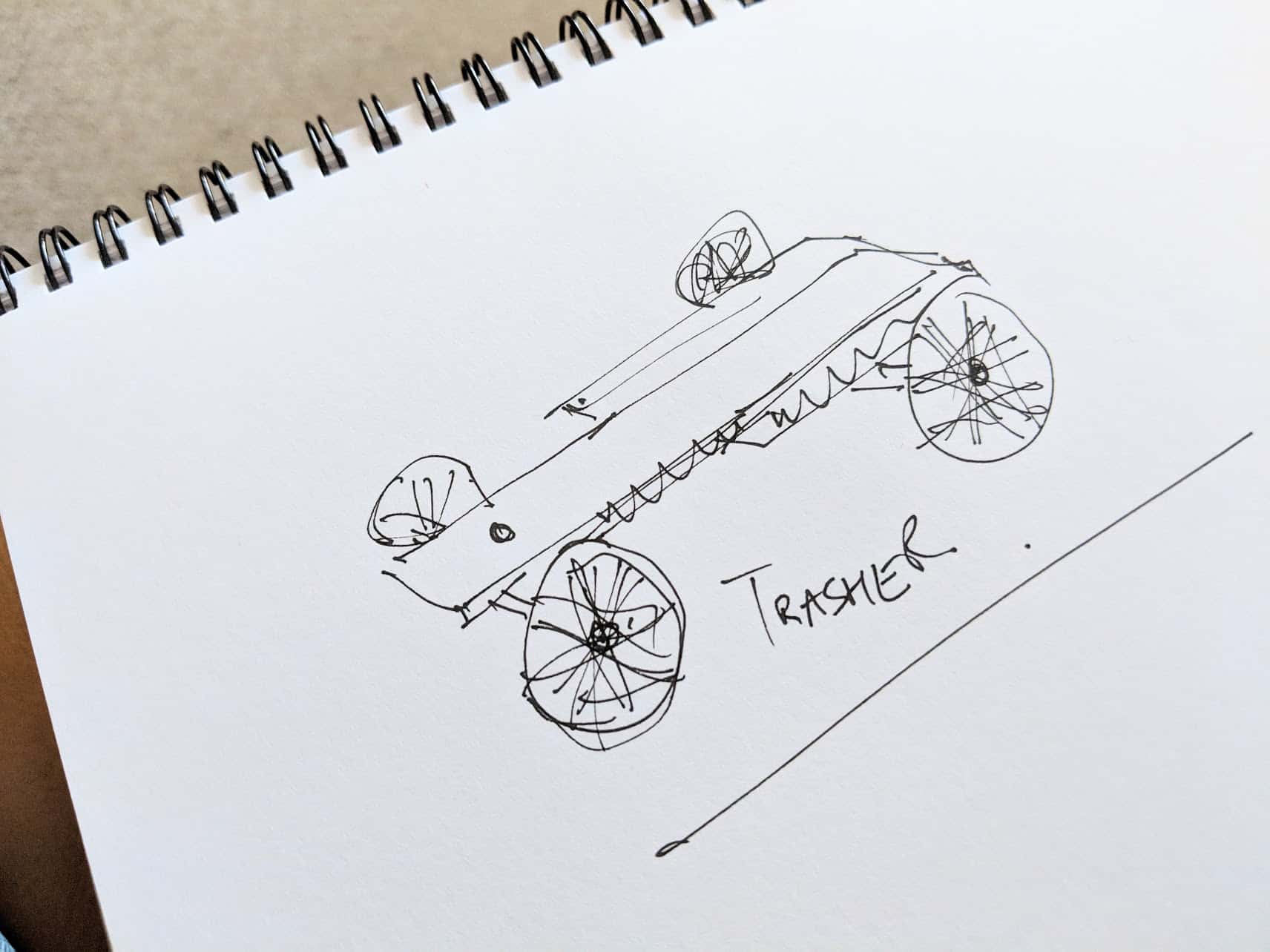

Now a trasher is not a common term but to me it’s a four-wheeled cart made from old pram wheels and some abandoned mahogany tabletop pieces; it is not someone who trashes things for wanton vandalism. I don’t know where the term came from beyond my dad but he called it a trasher so trasher it remains. As a kid with my brothers we’d find the steepest cobbled street and let go.

Of course this came into being long before making things from other things was called upcycling and well before it became vogue and boutique. We waited until after five when the dump men left the site and off we scooted with me on the trasher pulled by my dad. In those days there were no protective barriers and no safety signs or warnings either. The dump was unfenced and unrestricted. Unhygienically dangerous though it was, this rat infested mass was my playground on up through my teen years. For some unbelievable reason Stockport County Council took my nature world from me with the first truckload of Stockport refuse. My 300 acre sanctuary of catkinned pussy willows surrounding my ponds and springs became a cesspool of toxic waste and no one, no one, complained. This flat field with ponds filled of frogs, newts, toads, ducks, moorhens and coots gradually disappeared beneath an urban sprawl of waste. No more the field vole and the weasel, the kestrel’s home and the skylark high overhead. Eventually it became a hill piled high, covered with dirt to create an artificial hill. I didn’t altogether understand what was happening. I did know it seemed so very wrong!

The wood was birch plywood strips up to but no more than 4″ wide, half inch thick. Clean offcuts really. I didn’t know what plywood was until that moment of loading, but there was a mass of it for the taking. We loaded up the cart in neat piles that took all the pulling power my dad had with me pushing from the rear. Though my dad was no woodworker he set to with handsaw and hammer and nails while I watched the glue bubble slowly on the kitchen stove in a double burner made from a pan with a tin can inside. Once the glue started to drizzle slowly off the stir stick I waited for my dad to say it’s ready. With the narrow strips cross cut to length my dad glued and nailed the sections into tee sections that formed stems, feet and rails. He glued the sections and I held them from sliding with the glue in between. The glue dribbled from the joint lines as soon as he clenched the nails over on the inside faces. The long drips, hardened off, remained there and were never cleaned off. When we’d done my two sisters had bedside tables painted light green and pink (cans of paint from the same dump) to hide the nail heads and glue runs. I was so proud of my dads abilities!!!

Ihave always quite liked plywood. Its wide expanse of knotless beauty and stiff rigidity seemed somehow to defy the natural propensity of wood to expand and contract, shrink in the wrong places and split into problems where and when you least want them. I am too old to accept MDF for obvious reasons. It is the most insidiously hideous material under the sun, along with pressed fibreboard, chipboard, oriented strand board (OSB), flake-board and others. These past few weeks I have been developing an idea I first thought up many years ago. I’d shelved it for most of that time because it seemed counterintuitive to my ambition for woodworkers to rediscover what amateur woodworkers enjoyed in the early half of the last century–working wood, hand tools, the developing of skills. I don’t really know what happened during that same period but in the 1980s it seemed to me that I was visiting more and more benchless and toolless workshops. By that I mean the types of workbenches used were now lowered assembly benches, often without vises and such. These workshops had half a dozen machines that replaced hand tool operations—but did they really? No one I met seemed at all bothered at all; until I demonstrated using hand tools that is. Was I witnessing the demise of hand work? I think I was, going off what I saw. People seemed to be losing not just the skills and the significance of hand tools but also their own dextrous development in using them. Today I feel we may have turned a corner, primarily because the internet provides such an excellent platform for the little guy like myself. Oh I know there is a lot of junk to filter through to find the needle in the haystack but it is worth it when you need it. More and more woodworkers are discovering themselves. They, you, are becoming the modern day woodworking artisan. This is a most marvellous thing and icing on the cake would be if it could just keep spreading into all sectors.

The thing that separated plywood off from the pack was that hand tools can, with the slight skewing of different tool techniques, work really quite well with plywood but will never work well with other so-called engineered wood or boards. I can plane and saw plywood by hand and even work chisels to chop mortises, chisel out recess and pare surfaces. The important issue is be prepared to sharpen more often than with ordinary wood. This week I made my second workbench from plywood. It emerged from two and half sheets of 3/4″, 13 ply, birch plywood boards and follows my design for an English-style joiner’s workbench that’s well suited to joinery and furniture making. My success was creating a workbench without too much if any hand cutting of joinery yet having the same intrinsic strength and value of actual joinery throughout. It is in all essence a fully jointed workbench with housing dadoes and mortise and tenon joints yet no chisel touched either of the two joint types in the cutting of them.

Now the bridge.

Before anyone jumps on me for making a hand tool workbench using a machine, I think that there is good reason to. Because machine woodworking is a completely different form and sphere of working wood than woodworking with hand tools, the one is not remotely the same as the other. People who use machines often distance themselves from the reality and efficiency of hand tools and hand skills without ever realising the wonders of using them. Of course the same can be said in reverse except for yet another reality and that is that the majority percentage, perhaps as high or higher than 90%, of woodworkers, simply cannot have machines for them to use for a wide variety of reasons including cost, space, environmental unsuitability and several more. I have often had professional full time woodworkers in my classes who attended degree courses for years but had no more skill in hand work than the raw beginners working on benches alongside them. That has proven to be more common than not. That’s mostly true of woodworking teachers at university and college level also who had only a very minimal knowledge of hand tool woodworking.

Just as a bridge spans two distinctly opposite land masses to connect them, so too my newest workbench makes the connection between machine methods of working wood and hand tool methods–perhaps even the old methods with the new. In a matter of a few days, you can have a workbench you will not only be proud of but one that is as functional as any bench you might ever need. But you might want to continue through the whole project without a break. It takes about two hours to rip and crosscut the component parts into stacks for the bench top, aprons, rails and legs. With the measurements given it takes about three more hours to glue and clamp them into laminated sections. Fitting the leg frames should take half an hour for each one and gluing them up is simply enough for a 20 minute task max. Assembling the whole does not take too long either; an hour should do it. What does take time is planing and sanding to a good level. Maybe I should allow two hours for this. In a long day you should have the bench together. All that is left is the vise installation, an hour, and applying finish, two to three coats, another hour.